Here’s a riddle. Which technology am I describing?

Spreads false information faster than truth

Makes people intellectually lazy and dependent

Wipes out entire job categories overnight

Floods society with so much information we can’t think clearly

The answer is... obviously... the printing press.

The Monks Were Freaking Out

In the 1400s, a German abbot named Johannes Trithemius was having a meltdown. The printing press was sweeping across Europe, and he saw only disaster.

“He who ceases from zeal for writing because of printing is no true lover of the Scriptures,” he warned.

His concern wasn’t just about scribes losing jobs. He feared the technology would make people intellectually soft. Why memorise scripture when you could just look it up? Why cultivate spiritual discipline through hand-copying when machines could churn out books by the dozen?

To Trithemius, printed texts were fast food for the mind: cheap, convenient, and ultimately corrupting.

Cars Were Supposed to Ruin Everything

Fast forward a few centuries. The automobile arrives. Panic resumes.

Isaac Asimov put it well:

“It is easy to predict an automobile in 1880; it is very hard to predict a traffic problem.”

Critics saw the obvious dangers: faster transportation would isolate communities, destroy walkable towns, and scatter families across vast distances. They weren't entirely wrong. Cars did reshape society in ways that created new problems.

But they missed the bigger picture. Cars didn't just speed up existing transportation they also created entirely new possibilities. People could live in one place and work in another. Families could stay connected across long distances. Rural areas gained access to opportunities that had been locked away in cities.

The critics focused on what we'd lose. They missed what we'd gain.

Computers triggered the same cycle

When computers emerged, the fears restarted.

Journalist Sydney J. Harris captured the new fear perfectly:

“The real danger is not that computers will begin to think like men, but that men will begin to think like computers.”

The worry wasn't that machines were too dumb. It was that we'd become mechanical, rigid, uncreative.

Newsweek columnist Clifford Stoll was certain about computers' limitations. In 1995, he declared:

“No online database will replace your daily newspaper. No CD-ROM can take the place of a competent teacher.”

He was spectacularly wrong, but his fear was genuine: computers would hollow out real learning and human connection.

Now It's LLMs' Turn

Today's panic follows the exact same script. Large Language Models will destroy our ability to think critically and create creatively. We'll outsource cognition entirely. Students will stop learning to write. Programmers will forget how to code. If ChatGPT can draft emails and Claude can explain quantum physics, why develop any skills ourselves?

"But this time is different," the critics insist.

Recent studies suggest that overuse of AI tools might correlate with declining critical thinking skills. Some research indicates that frequent AI users show diminished ability to evaluate information critically or engage in reflective problem-solving. The fear is "cognitive offloading" i.e. becoming so dependent on AI that we lose the ability to think independently.

This concern deserves attention, but not panic. These studies capture real risks during the transition period, but they measure immediate effects, not long-term adaptation. We saw similar temporary dependencies with calculators and spell-checkers before people learned to use them strategically. The same pattern emerged with search engines where initial over-reliance gave way to more sophisticated usage.

The pattern is consistent: tools change how we distribute our cognitive effort, not whether we think.

The Logic Doesn't Hold

Cars didn't stop us from walking. We still hike mountains, run marathons, and take evening strolls. In fact, cars expanded where we could go, opening up trails and routes we never could have reached on foot alone.

Calculators didn't destroy our relationship with numbers. We still need mathematical intuition to know whether an answer makes sense, to estimate roughly what we should expect, and to frame problems correctly. Calculators handle the tedious arithmetic so we can focus on the interesting parts like pattern recognition, problem-solving, mathematical reasoning.

Spell-check didn't kill good writing. It freed writers from worrying about typos so they could focus on what actually matters: developing ideas, crafting arguments, finding the right voice, structuring compelling narratives.

Google didn't replace our need to know things; it changed what we need to memorise (less) and what we need to understand (more). We stopped memorizing phone numbers and started recognizing patterns in information.

How We Use LLMs Matters

The key lies in how we use LLMs and how we help others use them thoughtfully.

There's something troubling beneath many concerns about AI: elitist gatekeeping disguised as educational virtue. Critics argue that using AI for writing is "cheating" or will make students "lazy." But this often comes from people who already possess strong writing skills, advanced degrees, or native fluency in English. They're essentially saying: "I struggled to learn this the hard way, so everyone else should too."

This gatekeeping ignores reality. Not everyone starts with the same advantages. Some people have learning differences, language barriers, or simply lack confidence in their writing. LLMs can help level the playing field by giving someone with great ideas but poor grammar the ability to communicate effectively, or helping a non-native speaker express complex thoughts with clarity.

The real question isn't whether using AI is "authentic" thinking. It's whether we'll use these tools to expand human capability or treat them as thinking replacements.

Use them to augment thinking, not replace it. Let AI handle first drafts so you can focus on refining ideas. Use it for research summaries so you can concentrate on synthesis and analysis. Let it explain complex concepts so you can work on applying them creatively.

You still need to know what you want to achieve, evaluate what the AI produces, and shape it into something meaningful. The thinking doesn't disappear but it shifts to higher-level activities like judgment, creativity, strategy, and original insight.

History suggests we'll adapt, as we always have. The question isn't whether LLMs will change how we think (they will). The question is whether we'll actively participate in that change or just react with panic.

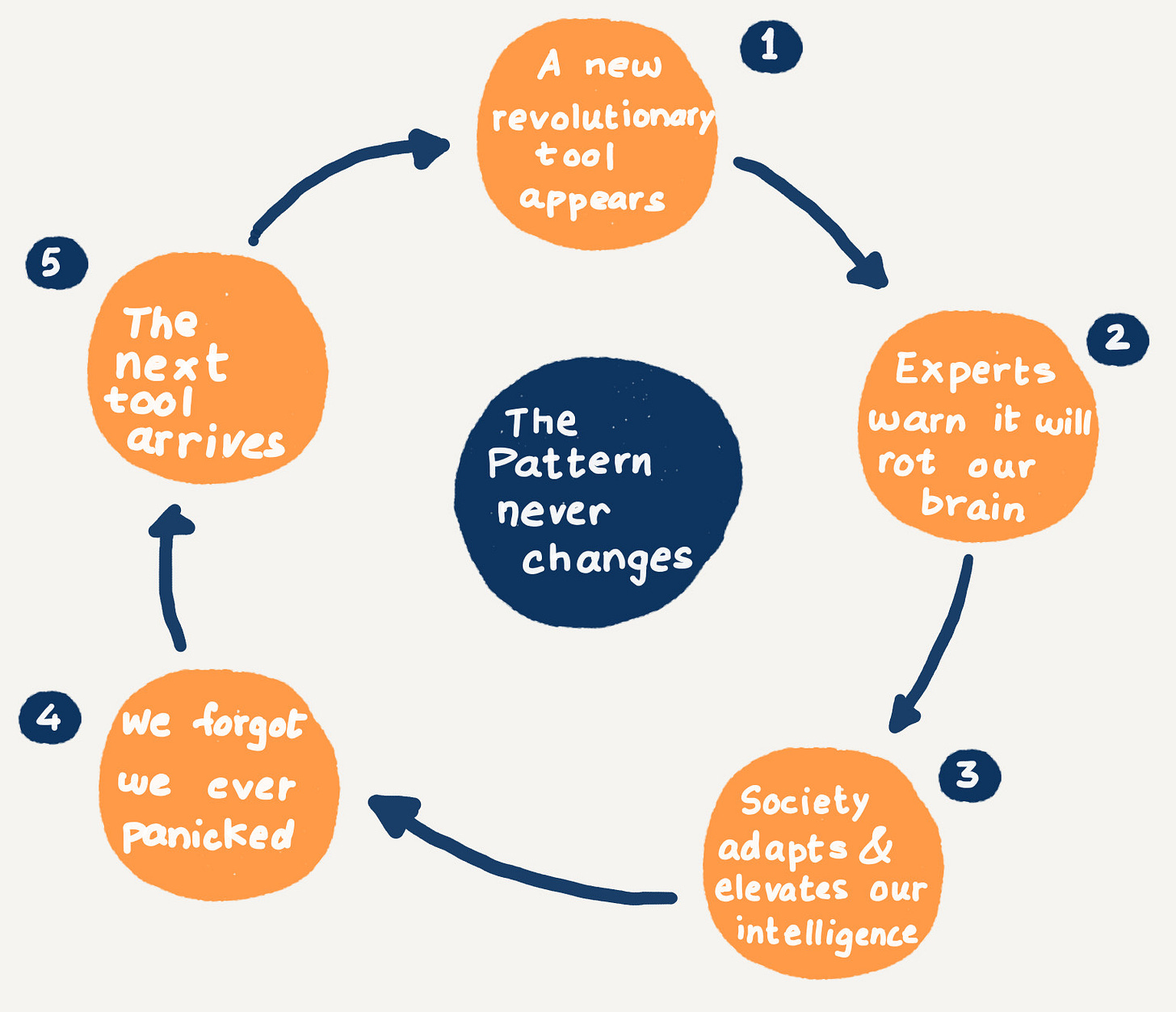

The Pattern Never Changes

Here is the cycle:

A new tool appears

Experts warn it will rot our brains

Society adapts and elevates human intelligence in new ways

We forget we ever panicked

The next tool arrives and it starts again

The Real Risk

The danger isn’t that AI will stop us thinking. It’s that we will believe it will, and stop trying.

This belief breeds passivity. We either reject AI entirely or submit to it blindly. Both paths waste the chance to shape this moment.

Every generation thinks its new tech is uniquely threatening. Every generation is wrong about the threat, and right that change is coming.

The real question isn't whether AI will reshape thinking. It is whether we will shape that reshaping, or just react with fear.

History suggests we are better at adapting than we think. The monks feared the printing press would ruin faith. Instead, it spread spiritual ideas to millions.

Maybe it's time to stop panicking and start building. The future belongs to those who shape it, not those who fear it.

Thank you for building a historical narrative around how past automation has impacted humans. I agree that panic is unnecessary, but we need a proactive action plan that begins in schools and emphasizes critical thinking and AI literacy. As with previous technological shifts, the key lies in guiding society to adapt thoughtfully rather than react with fear or blind acceptance.

We are dealing with two distinct groups of people regarding AI adoption. The first group will unquestioningly trust AI outputs, relying on their responses' convenience, speed, and polished authority without verifying their accuracy. Automation bias, cognitive laziness, and a lack of AI literacy will likely drive this behavior, as we have already seen with tools like Google or GPS. This passive reliance may reinforce risks like misinformation, cognitive atrophy, and blind trust in technology as an "infallible" source of truth.

The second group, however, will critically evaluate AI outputs, particularly in high-stakes life and business scenarios. Over time, this segment will grow, driven by education, cultural shifts, and encounters with AI's limitations (such as hallucinations or biased outputs).

For the majority, though, deliberate and sustained efforts are needed to prevent blind trust in AI from becoming the default behavior. Education systems must prioritize teaching AI literacy and critical thinking early, and developers must build tools that encourage verification and skepticism rather than passive acceptance. Without these intentional steps, we risk creating a society that amplifies the dangers of misinformation and over-reliance rather than harnessing AI’s potential to enhance human intelligence and decision-making.